Renaming, Book Signing Planned for Native American Collection

In 1847, Presbyterian missionary Henry Spalding acquired handmade Nez Perce artifacts and sent them from north-central Idaho to his friend and supporter, Dudley Allen, in Ohio in exchange for commodities. This was the fate of many early Native American materials, to be appropriated by non-Natives and removed from the hands and lands that created them. The shirts, dresses, baskets, horse regalia, and more—called the Spalding-Allen Collection—would not return to their rightful home until they were purchased by the tribe from the Ohio Historical Society in 1996 for $608,100.

This month, the Nez Perce Tribe will commemorate the 25th anniversary of the collection’s return with a June 26 renaming celebration and other events, including a June 19 panel discussion and book signing with Washington State University Libraries’ Trevor Bond. The renaming, panel discussion, and book signing will take place at the Nez Perce National Historical Park in Spalding, Idaho. For the full list of activities and video presentations, visit the tribe’s website.

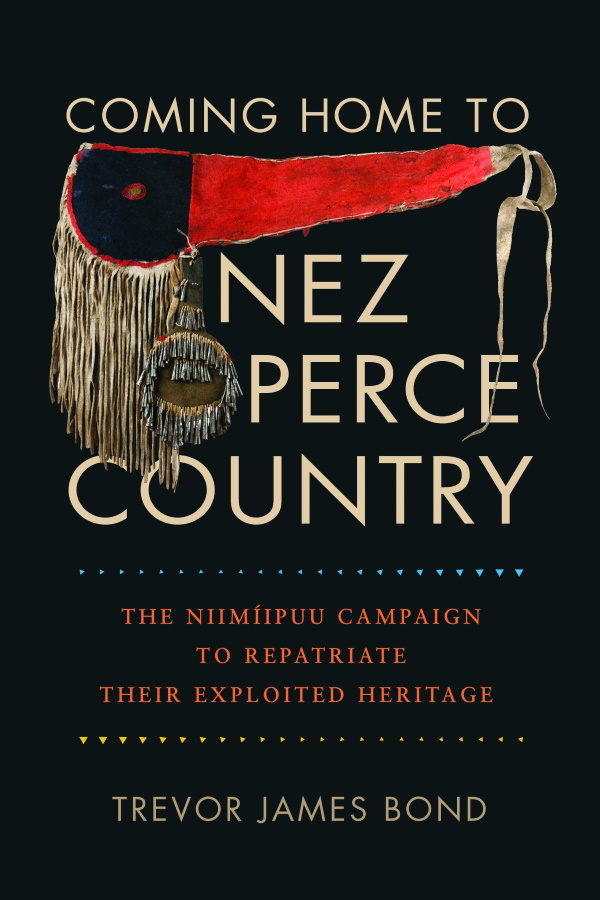

Bond’s book, “Coming Home to Nez Perce Country: The Niimiipuu Campaign to Repatriate Their Exploited Heritage,” published this month by WSU Press, follows the collection’s journey and how the Nez Perce Tribe reclaimed their artifacts through interviews with Nez Perce experts and extensive archival research.

Following Allen’s death, his son donated the collection to Oberlin College in 1893. Oberlin College in turn loaned most, but not all, of the artifacts to the Ohio Historical Society in 1942. The Nez Perce items were mostly kept in storage until Nez Perce National Historical Park curators rediscovered them in 1976. After negotiations with OHS, the park borrowed the collection until 1993, when the historical society notified park curators that the items must be permanently returned.

In late 1995, amid public pressure and more negotiations, OHS agreed to sell the collection to the Nez Perce at its full appraised value of $608,100 and gave the tribe six months to pay. The Nez Perce Heritage Quest Alliance mounted a brilliant grassroots fundraising campaign, according to Bond. One day before the deadline, the tribe met its goal.

Bond’s book also examines the ethics of acquiring, bartering, owning, and selling Native cultural history, as Native American, First Nation, and Indigenous communities continue their efforts to restore their exploited cultural heritage from collectors and museums.

“This is a tale of survivance, the resilience and enduring presence of the Nez Perce people to advocate for justice and the repatriation of their cultural heritage,” Bond wrote. “It is also an example of the contested ownership of a collection by an institution, the Ohio Historical Society, of the material culture of a far distant people, the Nez Perce. However, in this case, the American public sided with the Nez Perce and their supporters. Their success drew upon a close collaboration with the National Park Service, persuasion, and a sophisticated media campaign. In the end, the Nez Perce Tribe repatriated the earliest documented collection of artifacts of their people and the largest and best documented surviving collection of Plateau material culture.”

More about the book can be found at the WSU Press website. Bond, associate dean of digital initiatives and special collections at the WSU Libraries, is also director of the Center for Arts and Humanities and co‑director of the Center for Digital Scholarship and Curation.