‘Frauds, Fakes, Forgeries’ on Exhibit at MASC

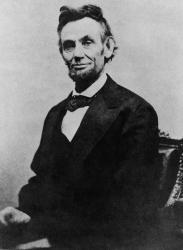

The manuscript from Honest Abe wasn’t so honest. It took more than 60 years for the staff of Washington State University’s Manuscripts, Archives and Special Collections to learn that the document was a forgery.

Part of an Abraham Lincoln collection purchased in the early 1940s, the handwritten fragment, entitled “On Administration,” was considered one of its chief attractions.

But in 2007, Daniel Stowell, director and editor of the Papers of Abraham Lincoln in Springfield, Ill., studied the sample of Lincoln’s handwriting and alerted MASC of its inauthenticity. Today, Stowell’s letter is part of the collection, a warning to patrons and scholars of the document’s shady history. MASC’s case isn’t unique either.

“The letters and documents of President Abraham Lincoln are the most commonly forged manuscripts in America,” said Trevor Bond, WSU Libraries’ associate dean of digital initiatives and special collections. “The manuscript expert Charles Hamilton includes 12 separate forgers of Lincoln in his book Great Forgers and Famous Fakes.

“There are so many fake Lincoln manuscripts, many held in academic libraries, that the only reliably authenticated cache of manuscripts is the collection that the Lincoln family donated immediately after his death to the Library of Congress,” Bond said.

Forgeries and other instances of skulduggery are the subject of a new MASC exhibit, “Frauds, Fakes and Forgeries: Deception in the Archives.” The exhibit opened April 17 and will run through July.

Stop the presses

Sometimes souvenir printings of newspapers are mistaken for original editions. Publishers often reprinted significant issues to celebrate anniversaries or as souvenir copies to distribute or sell. These facsimiles can often be confused with originals when they sit in an attic for decades and take on the appearance of an old newspaper.

“The original users of these facsimiles were well aware that they were reprints,” said WSU Libraries’ conservator Linnea Rash. “Over time, however, it became easy for later generations to assume that the historical newspaper that had been passed down through the years was an original. These items were usually not created with the intention to deceive. Their status as facsimiles has simply been forgotten.”

MASC has six reproductions displayed in the exhibit of an Ulster County Gazette front page dated Jan. 4, 1800, publicizing George Washington’s death. Only two known originals of the issue exist, according to WSU Libraries’ manuscripts librarian Cheryl Gunselman, yet thousands of reprints have circulated since the first president died.

To authenticate an old newspaper, one place to start is the Library of Congress’s Information Circulars webpage.

Beating a book thief

In 1987 and 1988, WSU and academic libraries around the country reported the theft of rare archival holdings. In MASC, staff found that 357 rare books and 2,500 manuscripts were missing, including the Collectarius Super Librum Psalmorum, printed in 1488. All told, the WSU materials were valued at roughly $500,000.

WSU Police Officer Stephen Huntsberry investigated the case; his work and help would eventually lead to the arrest of Iowa book collector Stephen Blumberg in 1990. When FBI and other law enforcement officials entered his home, they found more than 23,600 rare books and other materials from 270 universities and museums in 45 states, two Canadian provinces and Washington, D.C. Their value was initially estimated at about $20 million, later changed to $5.3 million — the largest book theft in U.S. history. Blumberg was subsequently tried and convicted in 1991 and sentenced to six years in prison.

Blumberg escaped notice successfully because he took care to remove signs of ownership from the books he took, Bond said. He sanded off library marks on the spine, removed book pockets, alarm strips and other ownership evidence. His method to remove book plates was to lick them off and then replace them with fake University of Minnesota Library bookplates he carried with him. But WSU recovered almost all of its stolen holdings.

“A key reason WSU was able to retrieve all but three of the more than 300 books stolen is that we had detailed cataloging of the books, noting unique bindings, inscriptions and book plates that allowed authorities to identify our books even when Blumberg took steps to erase WSU ownership marks,” Bond said. “[MASC’s] Julie King contributed to this cataloging along with retired staff member Leila Ludeking.”

“Frauds, Fakes and Forgeries” was curated by MASC staff, including Bond, Rash, Gunselman, scholarly communication librarian Talea Anderson, special collections librarian Greg Matthews and university archivist Mark O’English.

—Story by Nella Letizia