Couple’s Ancestry Search Leads to Nash Photos of Yakima Valley Farm Workers

It started with a search for a newspaper photo of an uncle with former U.S. Attorney General Elliot Richardson, taken at the Green Giant plant in Grandview, Wash., in the early 1970s. Laura Solis knew the history of her uncle, that he, her father and their family traveled from south Texas every year to do agricultural work in Washington. The photo was somehow tied to farm worker housing, her dad recalled. Solis wanted to find this meaningful piece of family history.

Her search led to an even more important find: the images of a Seattle photographer who documented the life of Latinx farm laborers in the Yakima Valley from 1965-1975, a time when dismal working conditions and meager wages for the country’s migrant workers featured prominently in national news. The Irwin Nash Images of Migrant Labor Digital Collection is housed in Washington State University’s Manuscripts, Archives and Special Collections (MASC).

Only a fraction of Nash’s 12,500 photos is digitized, but what they revealed to Solis was enough. The mission to find a family photo became one of preserving Nash’s images of regional and cultural history. She, her husband Mike Fong, both of Seattle, and other community members are donating funds to support digitizing the full collection, matching an $8,000 digitization grant WSU Libraries recently received. The Washington Digital Heritage grant is supported with Library Services and Technology Act funding provided by the federal Institute of Museum and Library Services through the Washington State Library, a division of the Office of the Secretary of State.

“We both know how much these photographs would mean to the families of the people depicted in them and how important they are to preserving the history of farm workers in the Yakima Valley,” Solis said.

Lipi Turner-Rahman, manager of the Kimble Digitization Center in WSU Libraries, will direct the digitization of the Nash photos with Mark O’English, university archivist in MASC, and Suzanne James-Bacon, electronic resources and MASC technical coordinator. Turner-Rahman sees the project as an extension of WSU’s land-grant mission.

“WSU is committed to preservation and worldwide open access to materials that document the lives of oppressed and neglected communities,” she said. “By digitizing and freely making this collection available online, WSU Libraries intend to augment the narrative of Washington’s largest minority group and add their stories, voices and images to the complex narrative of Washington’s common heritage.”

The invisibility of agricultural workers

Before finding the Nash collection, Solis and Fong searched through microfiche databases at the University of Washington’s Suzzallo Library for back issues of the Yakima Herald. The couple went through three years of the newspaper starting in 1969 looking for Solis’s uncle’s photo and accompanying story. They found neither. Then COVID-19 forced the library to close.

Solis, who grew up in the small town of Granger in Yakima County, was disheartened by the absence of stories about the area’s farm workers as she combed through the Yakima Herald accounts. It hit close to home: Like her father, Solis’s mother and family members also worked the Yakima Valley fields. The pair met and married in the valley in the early 1970s.

“There were sections of the paper devoted to personal and community stories, but they never featured the lives of the people who came to Washington to work in the fields,” she said. “Looking through that lens, it was surprising and sad to me that agricultural workers were not seen as being part of the community because I knew the other story.

“Agricultural laborers weren’t merely present; they were living and thriving and creating communities of their own that are the basis of the communities that are there now,” Solis added. “The focus on agricultural workers as a problem to be solved had the effect of making them invisible as people.”

‘They give me back the truth’

The partially digitized Nash collection, which Fong found when the couple’s search turned to online resources, filled in the missing pieces. Photos of weddings, dances, theater productions, rural women and agricultural labor revealed the rich and complex social, cultural, political and economic life of the Yakima Valley migrant laborers, according to Turner-Rahman.

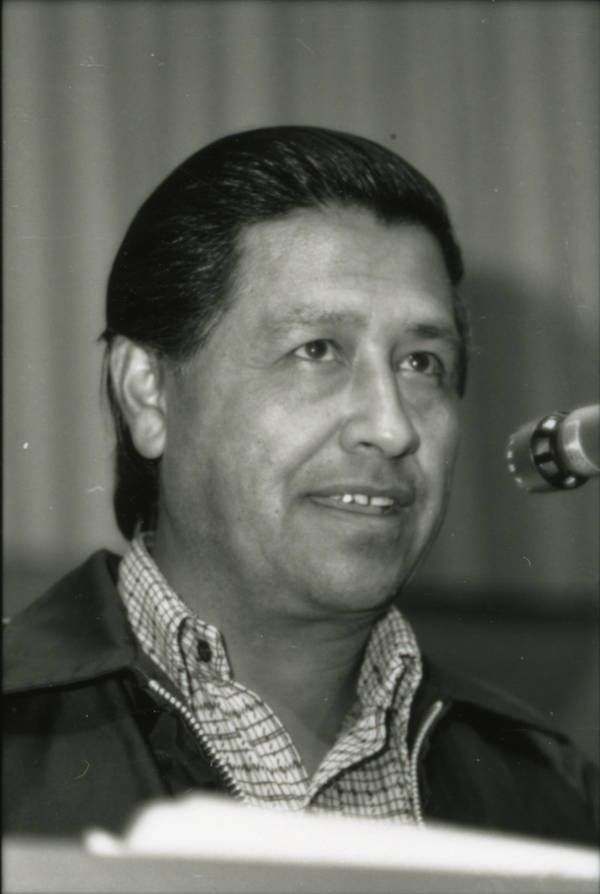

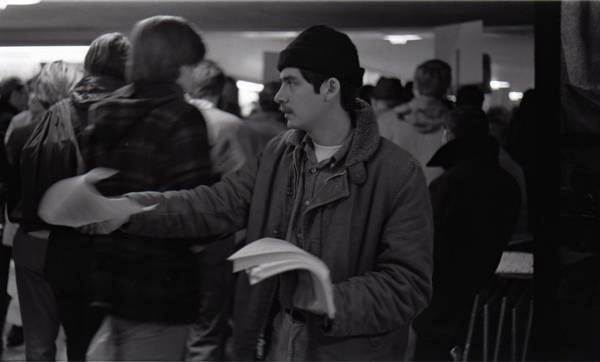

Nash had also captured the rise of justice for migrant farm workers and labor movements within the Yakima farm and migrant worker community, she added. He photographed farm worker rallies, the urban Chicano youth movement at UW and the collaboration between Latinos and black student unions picketing at UW and at grape protests. Of particular interest to researchers are photographs of visits by United Farm Workers (UFW) founder Cesar Chavez to farm worker rallies and Washington community organizers Guadalupe Gamboa and Tomas Villanueva.

“Here were the people that were missing from the newspaper articles,” Solis said. “Here were the experiences I remembered with my parents, brothers, aunts, uncles and cousins. The people in the photographs might even be members of my family. Above all, the photos show the humanity that had always been there. They give me back the truth about the place and the people I came from. They are beautiful and touching beyond words to me.”

Solis and Fong have since created a Facebook page to preserve the history depicted in Nash’s photos. Their goal is to link to stories as well as the images and follow up with anyone who comments to document a fuller backstory of the people in the pictures.

The couple also teamed up with Turner-Rahman, O’English and WSU Libraries’ development director, Dawn Butler, as well as Gamboa, to support the digitization of the remaining 12,400 Nash photos so others can see the complete picture of Yakima Valley farm workers. Visit the WSU online giving page to join Solis, Fong and others who donated gifts for the digitization project.

“I did not know about these stories growing up in Granger in the late 1970s and 1980s,” Solis said. “I did not know about Lupe Gamboa, Tomas Villanueva or the others involved in the events in these pictures, or even that my relatives may have been involved. The location of La Escuelita [the school for migrant children during those decades] is now the Granger Public Library, which is across the street from my grandmother’s house. There is a tiny museum about Granger within the library, but to my knowledge this history is not preserved there or anywhere else.”

Recollections of a future organizer

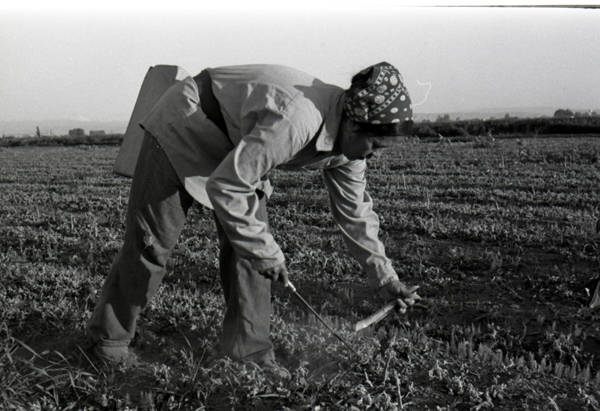

Nash photographed Gamboa handing out leaflets in 1968. In a video interview for the Seattle Civil Rights and Labor History Project, Gamboa recalled growing up in the late 1940s and early 1950s, working in the dusty fields of the Yakima Valley and hearing the stories of other farm workers engaged in the hard business of harvesting the nation’s food. Asparagus proved an especially difficult crop; work started at dawn because asparagus had to be cut early, and the backbreaking toil continued under an unforgiving sun with no cover until dusk.

For all that monumental effort, farm workers received poor wages—they weren’t covered by minimum wage requirements, unemployment insurance or benefits. They were also vulnerable to individuals who cheated the workers, the fraud running unchecked by the absence of regulation. The seasonal nature of the work forced farm families to go where the crops were, moving through a circuit of other farms and other states to bring in sugar beets, mint, green beans, and cotton.

“We would work as a family unit, and everybody would get the same wage,” Gamboa said. “My father, who had been working as a farm worker for 30 or 40 years and was very good would get the same wage as myself who was 13 or 14 years old. There was no differentiation. That’s why everybody had to work. Working together, you’d make a living wage.”

Organizing in the Yakima Valley

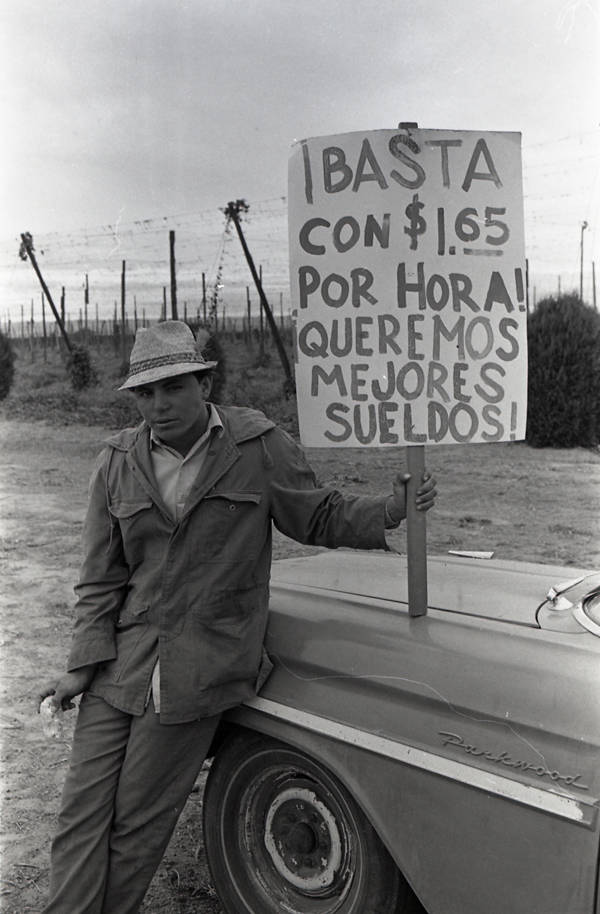

Fast forward to 1970, when Gamboa helped coordinate a series of strikes for higher wages on hop operations in Granger and the surrounding area. Men were paid $1.50 an hour, while women earned $1.25 doing the same job. The local farm workers seeking better conditions took their lead from the UFW in California. Eventually, the Yakima Valley strikes would disrupt the operations of between 14 and 16 hop ranches. More importantly, they laid the foundation for an organized farm workers movement in the region and state.

“This hadn’t happened before,” he said. “The growers had been used to very docile Mexicans.”

Despite that early success, organizing efforts in the Yakima Valley took more than a decade to coalesce when the newly formed UFW of Washington State held its first strike at Pyramid Orchards in early 1987. During that hiatus, Gamboa worked for the national UFW in urban U.S. cities and Canada before returning to eastern Washington in 1977. He served as a paralegal helping farm laborers with workers’ compensation reform and finished his law degree from UW.

But the farm workers’ continued plight and the need for a UFW presence in the Yakima Valley re-energized Gamboa and other activists in rallying support for farm workers’ rights.

“Culture played a very important part,” he said. “We had corridos [popular narrative and poetry that form a ballad] on the Mexican radio stations across the border talking about the benefits of the union and appealing to the culture and history of the workers, identifying how they were similar to Benito Juárez, Emiliano Zapata and Pancho Villa, who had fought for their rights. So we did utilize the cultural element.”

‘I just went in there to show what was going on’

A commercial photographer and Seattle native, Nash received his undergraduate degree at UW. His first trip to the Yakima Valley was to the Ahtanum Labor Camp, where he photographed the Latinxs and the conditions that they lived in. He also went to the Crewport Labor Camp near Zillah, Wash., and made several subsequent return trips to the Yakima area.

When asked in a 1989 oral history interview why he wanted to do these types of projects, Nash replied, “I just went in there to show what was going on. To try and illustrate what was happening to a segment of the population that at best might have heard about it third hand, that’s all.”

Digitization and publication of Nash’s photographs will make them available to scholars and students at any time and from anywhere, Turner-Rahman said.

“The digitized collection will be of vital scholarly interest worldwide and give scholars access to formerly unavailable material on Washington’s Chicano populations’ everyday life, as well as their political, social and financial aspirations,” she said. “It will foster new research and research questions from a variety of disciplines and fields on converging issues, including social and political movements, migration, Diasporas and history.”

—Story by Nella Letizia