MASC exhibit explores Indian boarding schools’ effect on Paul family

The cultural and multigenerational effects of Indian boarding schools on one family’s history is the subject of a new exhibit in WSU’s Manuscripts, Archives and Special Collections. The exhibit runs through mid-March.

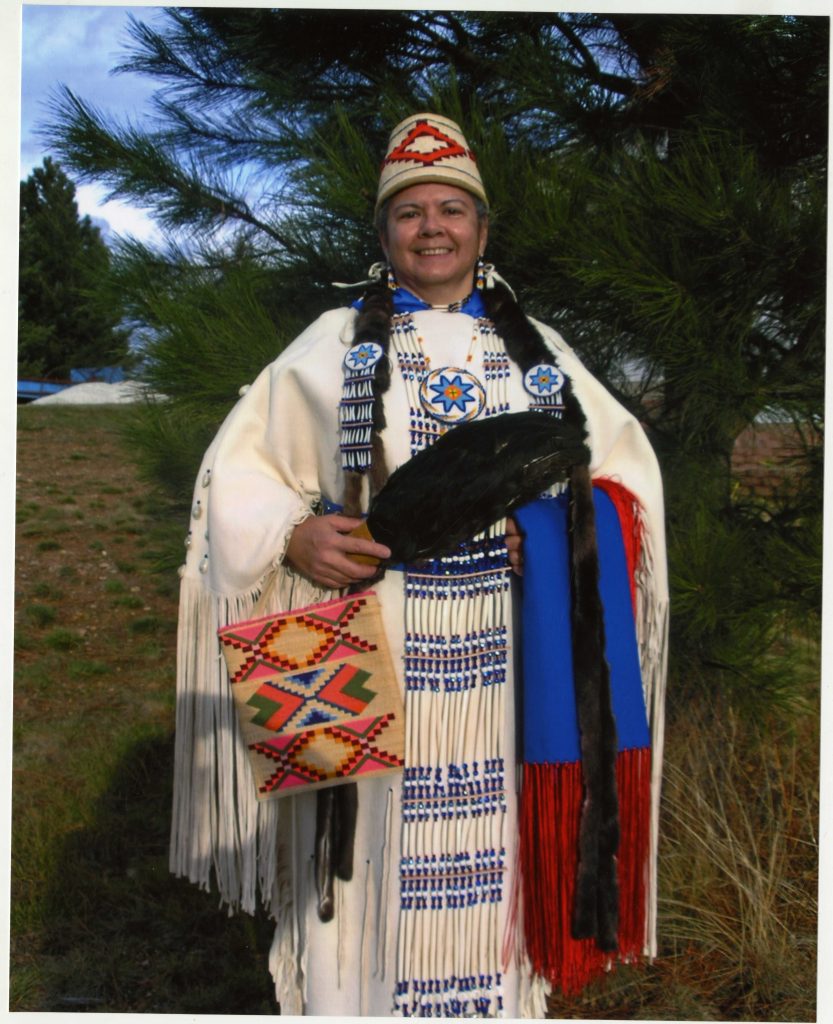

The exhibit is curated by Robbie Paul, retired director of WSU Native American health sciences in Spokane. Paul documents three generations of the Paul family and their experiences in Indian boarding schools beginning in 1880 with her grandfather, Jesse.

Just one aspect of trauma

The boarding schools were not the first places where cultural trauma to her family occurred. Paul also chronicles the early history of her great-great-grandfather, Chief Ut-Sin-Malikan, the first to see the loss of the old Native American ways and of Nez Perce identity in his lifetime. Her great-grandfather, Wa-Tat-Ooy-Napt-Lah-Hayne, and his family were in the Nez Perce War of 1877. In the Battle of Big Hole on Aug. 9, 1877, Wa-Tat-Ooy-Napt-Lah-Hayne and his wife, Um-Al-Wat, lost two of their six children. Wa-Tat-Ooy-Napt-Lah-Hayne and three more children died during and after the forced march to Indian Territory in Oklahoma.

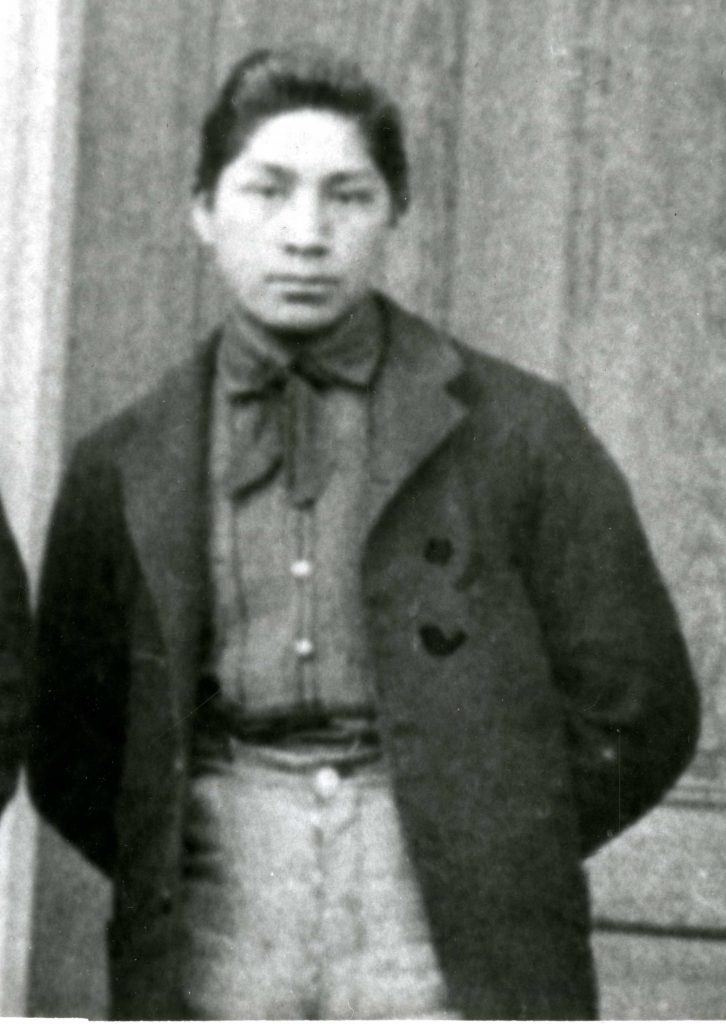

Um-Al-Wat’s only surviving child, Ka-Khun-Nee, was selected to go to Carlisle Indian Boarding School in Pennsylvania at age 10. There, he was stripped of his buckskins, his hair was cut short and he was given a bath with lye soap and a stiff wool uniform. He was also given a Christian name, Jesse Paul, chosen from a list of Christian names. For the next eight years, until July of 1888 when he graduated from Carlisle, Jesse was immersed in white culture while still retaining his knowledge of Nez Perce language.

Living the trauma in the present day

Robbie Paul said she often felt an uneasiness near the anniversary dates of her family’s past traumas. On Feb. 20, 1993, the day in 1880 when Jesse arrived at Carlisle Indian Boarding School, Paul was at a Spokane conference on suicide prevention for Native Americans. During a showing of a documentary on Carlisle called “In the White Man’s Image,” she learned of the details of the children’s introduction to boarding school life.

“It made me sick to my stomach,” Paul said. “I had to run out of the conference.”

She discovered other details of Jesse’s life and that of his mother, Um-Al-Wat. To keep her son connected to his Native American identity, she sent her son to boarding school with a medicine bag. Paul wondered how Jesse’s mother let go of her remaining child to make his way at Carlisle.

“She sent him with love to learn what he could to bring back help to his Nez Perce people,” she said. “Jesse had to have spiritual strength to survive.”

Healing cultural wounds through storytelling

In June 1967, Paul went to Haskell Indian Junior College in Lawrence, Kansas, for the summer, which was run in much the same way as her ancestors’ boarding schools. She attended classes but was also assigned work, such as cleaning the floors of the student union building.

“The Indian policy was still to assimilate the Indian into dominant society,” Paul said. “Those experiences helped me to relate to the experiences of my ancestors.”

Paul found that learning about the experiences of her family helped heal the wounds of the past. Telling their story “is the healing journey,” she said.

So is forming a truth reconciliation commission around Indian boarding schools and their practice of erasing Native American culture from their students. People are still dealing with the effects of this practice in the present.

“Healing isn’t going to begin until the truth is spoken,” Paul said. “We need to acknowledge that the damage happened. It was harmful to multiple generations.”

— Story by Nella Letizia